Alone in the Body: Marsha Recknagel’s review of Bodywork by Eva Tuschman Leonard

Bodywork

By Eva Tuschman Leonard

Bored Wolves co-edition with Firehouse Press (San Francisco), 2025

The first line of Eva Tuschman Leonard’s memoir, Bodywork, is a simple, declarative sentence: “The body is our first and final home.” What follows is anything but simple. Her memoir, a fusion of prose, poetry and visual art, is a record of how she not only lived through but navigated the before into the after of her life. It’s a riveting account of her “frantic search” for a way not only to withstand pain but to make meaning of what has happened to her. Her dilemma is evident in her question to both herself and us: “But how could I turn away from my body when it was the only home I had ever known?”

The power of the first section, a lyrical prose piece, contains echoes of the familiar mythic tale of exile and quests. Her quest? To create a new narrative of herself, to put the puzzle pieces of her identity back together, to bring light to the dark that descended when she was in her vital, creative midlife. Leonard’s story begins with a description of the sudden onset of severe, often incapacitating pain. She writes of “searing bouts of electric shock-like pain” traversing the left side of her body. The neurological onslaught moves from her brain down the left side of her face, continuing its descent to her feet. The descent becomes a metaphor for where she has plummeted in all ways, physically, spiritually and mentally.

In a faint echo of Dante’s Inferno, Leonard tells us of “the slow-motion avalanche” which delivered her into an “underworld” where there was “no clear escape route.” Her illness has, she says, fractured her identity and dissolved her coherent concept of self. One reels along with her as she describes how the enigmatic illness shifted the foundation of her belief systems, her trust in the vision of her future, and even her faith. Separated from who she once was by what she describes as a quicksand of fatigue pulling her under, she writes in piercing detail of her struggle to save herself. Within her sculpted sentences one can feel the anguish of a woman who stands inside the rubble of her past self and asks us to bear witness to her tale, the story of the total upheaval of her life by a “mysterious, unnamed disease.”

With the turning, turning of her agile mind she contemplates the myriad ways she could manage to live in the thrall of a chronic, inexplicable illness. Surrender, but not completely. Learn to see it as a blessing and a curse. Love yourself. Keep vigil over yourself through the dark times of the pain. Learn to live in the dark. Learn to see in the dark. Practice her own death. Rebuild yourself from the ruins of yourself. Become one with mystery, live with no boundaries between “this form I call my body and the cosmos.”

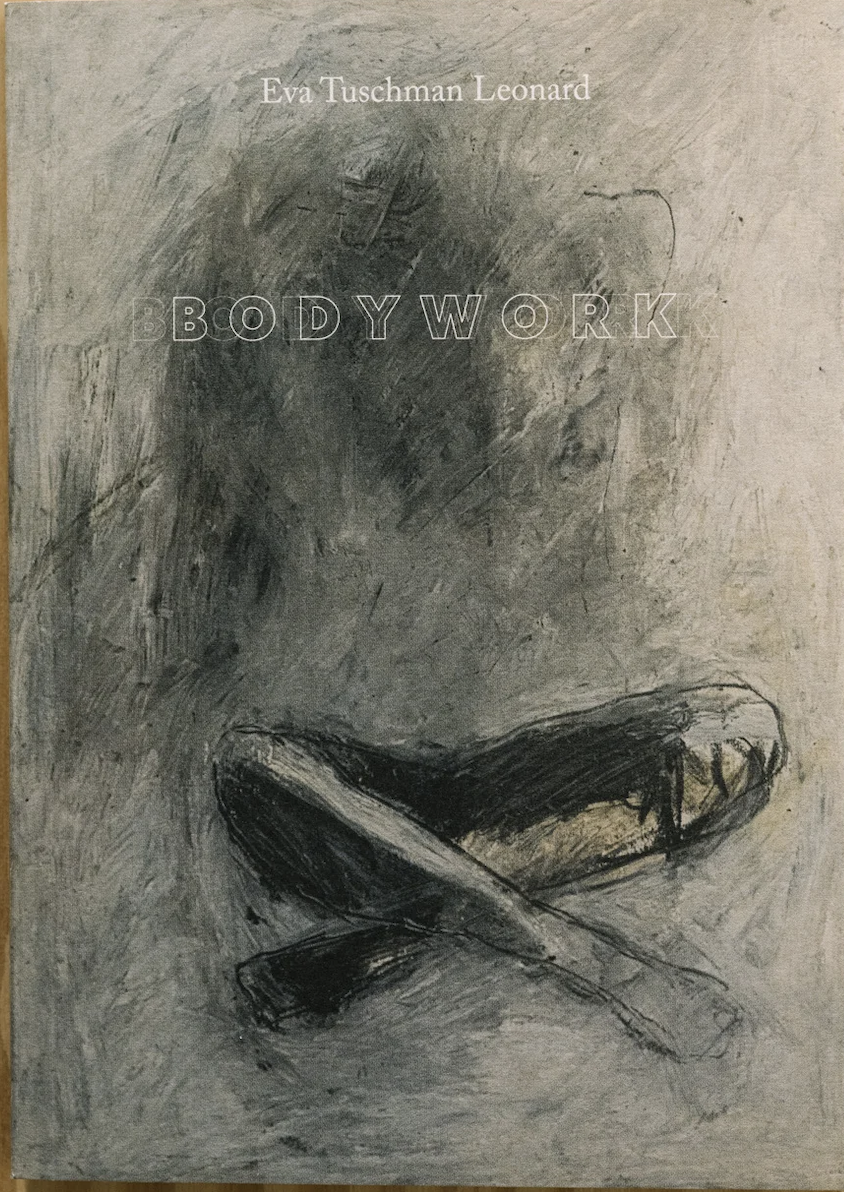

Leonard brings forth a holistic vision through the prisms of prose, poetry and drawing. By such division and juxtaposition, we are given an immersive experience, a writer’s equivalent of surround sound. The drawings, self-portraits created in her teens and twenties, were “rediscovered” in a “personal archive,” reproductions of which are interspersed throughout the book. The mysterious unearthing of a batch of self-portraits brings to mind other tales through the centuries of papers secreted away, and when found, become revelatory. She was, she says, “astonished how they made visible the invisible experience of illness in the body.” They seem to her, as well as to me, uncannily prophetic. The portraits are of contorted bodies marked as if scored by lashings of bold black marks which crosshatch the naked or robed figures. Not all of the figures are imprisoned by scratches, but the faces are always smudged, lacking discernable features. Feet, legs, and arms obey no boundaries as one appendage blends into another as if there’s been a human game of pick-up sticks. It is difficult to distinguish which is leg, which is hand. If I’d not been told the drawings were created decades before the onset of her illness, I would have assumed they were drawn specifically to illustrate the book. They are a perfect visual representation of the stranglehold pain has on Leonard’s body.

To “host” a chronic illness, particularly an autoimmune disorder, whereby its definition the body has turned on you, is to face the existential truth that one is alone in one’s body. “No one lives in your body but you,” she writes in a simple but profound statement about our human plight. When stricken with illness, Leonard became, in her mind, exiled from the world Virginia Woolf called “The Army of the Uprights.” In the acknowledgements, she writes of her editor as someone who threw her a “lifeline of connection” when Leonard felt “the most exiled from the world” around her. When her editor encouraged her to write of her experience, she was surprised her editor thought she might have something to report back. She has reported back.

Following the prose/poem/preface, she stops the flow to step out and directly address the reader, expressing frustration with the linearity of prose, feeling it failed to mirror her experience of life with a long-term illness. Too linear. Too predictable. Concluding that the fragmentary comes closer to her target, she extends an invitation to “Enter the beautiful nightmare” of the next sixty pages. What follows are the phrases from her notebooks, some in poetic form, and some prose of short paragraphs. The phrases are sometimes too aphoristic for me. More often they are like darts to the reader’s psyche, causing full body chills or a wincing retreat. An inveterate journal keeper, she brings forth what she calls “fragments of daydreams and nightdreams, reveries and desires. Of unlearning,” Initially cranky about the adjustment required to enter the more enigmatic section, I resisted. I leave the book, come back to the book, and continue the pattern until, to my surprise, my resistance dissolves, and I slide into the poems and phrases. The distance between me and her, the writer and the reader, narrows, and I am no longer a witness but her close companion in the “strange territory” where she dreams she is asleep, where her physical body is no longer present, where she looks on from a “spiritual vantage point.” Sometimes one line is as moving as whole paragraphs. “Through my wounds I have found new worlds….” I grasp at the more hopeful lines. I brace myself as I read just as I imagine she does in her life, waiting for the next darkness to descend.

In her story, the narrative arc we are accustomed to as readers is disrupted, just as Leonard’s life has been. The story of epiphanic triumph is not possible when one lives with chronic illness. The pilgrim’s progress will not be hers. My heart sinks when I turn a page near the end of the book to read, “Apprentice to my own disappearance/I watch myself descend/Arm and legs suspended.” Yet on the very next page she writes, “Finally feeling at home with/Not knowing/Dancing with mystery.” The victories are no less real for not being sustained. We experience with her the mental balancing act she must strive for as the pattern is repeated relentlessly. Equilibrium is achieved, then lost. Attained, then lost. She is, though, still standing, the book’s existence a testament to her survival and strength.

Leonard wrote she hoped in sharing her vulnerabilities, others might be less lonely in theirs. Her voice was in my head for days, a voice who had stories much like my own. Several times while reading Leonard's descriptions of the pain, I had to take deep breaths. Like Leonard, I am an artist. I am a writer. I have Multiple Sclerosis. After my diagnosis, I went into a dark place, a stranger to myself, my dreams of a future blown to bits. I could relate to every finely-wrought sentence in Bodywork, every description forged from her pain and sculpted with specificity brought corresponding grief to the surface. When she asks herself, “What can she do but love and accept her body?" I felt the question was asked of me. It was two in the morning. I’d been immersed in Leonard’s world for hours, days even, and my boundaries had dissolved as I struggled to do the work justice. I had the sudden urge to leap up, stretch my legs, and walk away. I stepped out onto the front porch and into the night. There were fireflies. Still her voice was with me. I stood, staring at the night sky, swaying a bit because I didn’t have my cane. I envisioned the lifeline her editor had thrown out, pulling Leonard up and out of the quicksand to deliver her above ground. Judging by the acknowledgments, she has had “steadfast friends” throughout that have thrown lifelines, a stark contrast to the lines crisscrossing the bodies in the drawings, which call to mind bondage.

Near the end of the book, Leonard tells us body work is actually “soul work,” the process by which she wrestles with the loneliness of embodying “a body hijacked by illness.” “Embodiment/a blessing and a burden” is in the text as well as on the back cover. The book’s dedication is to her parents, whom she says taught her “from her very beginnings how to engage life through creative process. “Because of you I can transform every experience into art.” Bodywork is the history of such a transformation. The book, published by Bored Wolves Press and Firehouse Press, is an exquisite object of art in and of itself. Clearly the process of writing Bodywork and the connectivity it engendered enabled her to choose to close with this: “Despite everything/I still believe in the holiness of the body.” A hard-earned ending, even more eloquent paired with a spectacular drawing of a body upright, engulfed in either flames or an ethereal cosmos shower, head and arms reaching up until outside the confines of the page.

Marsha Recknagel, a teacher, writer and artist, taught literature and creative writing at Rice University for twenty years. She has a Ph.D. from Rice and an MFA from Bennington Writers Seminars. Her memoir, If Nights Could Talk was published in 2001, selected that same year as the Common Book for Houston Community College, and was adapted for a movie by Hallmark Hall of Fame. Her work has been published in Gulf Coast, the Columbia Review, The Journal, and MicroLit. Her art work, selected for several juried shows, has been exhibited in North Adams, MA, Bar Harbor, ME, Boca Grande, FL, and East Hartford, CT. She lives in Williamstown, MA.