A Fellow Pilgrim: A Review of David Ferry’s Some Things I Said by Les Schofield

Some Things I Said

By David Ferry

Grolier Press

The recollected works in Some Things I Said displays David Ferry’s lyrical prowess. In homage to his wife, Anne Davidson Ferry, he uses each stanza of his title poem to stitch together poetry he has written or translated, as well as a poem by Wallace Stevens, and creates a contextual anthology for his enigmatic lines. The works in this extraordinary volume fulfill the expectations for transformative poetry stated by a former professor of mine: Why read anything? To learn, to be amazed, to come away understanding something elusive. It’s the music and depth found in poetry, the brevity, the invitation to ponder. Ferry delivers on all counts. One example is his response to the poetry of Marianne Moore:

To squeeze from a stone its juice

And find how sweet it is

Is her art’s happiness

In the brief verses, Ferry creates enough music and depth for months of pondering – a feat he accomplishes in all these poems. Ferry’s lines pulsate with the experiences the words intone, surprising the reader with their sensual substance and the shape of each poem. This passion to create lines that sing was mastered throughout his long life as a teacher and a poet in constant collaboration with his wife. Some Things I Said is wonderfully instructive, a poetic masterclass for any aspiring or seasoned poet.

The profound depth of this compendium, however, is in the unique anthological poem that gives this book its title. A reader might assume that the verses of this poem are nothing more than a table of contents. Indeed, George Kalogeris mentions in the afterward that Ferry suggested that this was the poem’s function. But a careful reader will quickly suspect that Ferry is cleverly applying his version of Frost’s assertion of ulteriority. Given his wife Anne’s extensive treatment in The Title to the Poem on the way poets use titles to shape a reader’s experience of the poem, it would be expected that as a table of contents, Some Things I Said would be composed of each poem’s carefully considered title. Ferry credited Anne with creating the titles for most of his poems and was keenly appreciative of her insights on how poets use titles to shape the reader’s experience of the poem. Therefore, it is intriguing that Ferry seems to disrupt the titles’ function by extracting lines from within each poem often with subtle changes to the wording or fusing lines that do not appear together as originally written, and then offsetting these lines next to the referent poem. Ferry’s grief over her death is keenly felt and expressed throughout, giving the sense that Some Things I Said is an elegy:

Right there before my eyes was the one who said

Where are you now? Where

Are you Anne? I was the one

When this poem was published, David Ferry was ninety. The form of its lines suggests that the poem voices Ferry’s reflective valuation of his own significance. The tense of his “I said” makes clear that these are the words of a man looking backward over his life’s journey. The emphatic “I” asks that we attend to what he is saying in this moment while he quotes these lines as assertions of their significance, the defining moments of his life. In addition, Ferry, renowned for his proficiency in iambic pentameter, brazenly abandons his preferred metrical pattern for shards of free verse.

Some Things I Said is, in fact, an invitation to draw alongside Ferry as he adds his part to the age-old song of humanity celebrating triumphs, enduring tragedies, and lamenting mistakes in the context of wonderment and ultimate puzzlement. In the gorgeous introduction to his translation The Georgics of Virgil he admits to this task:

“But men are unlike the other creatures in having the obligation of learning to know most fully what their labor is, how it succeeds and fails, and in having the obligation of knowing how to sing about it.”

It is a testament to his extraordinary brilliance that this poem has the power to pull us through his written words and into his remarkable voice. It evokes the image of an older man sitting at a coffee table with his aged friends recounting past exploits with their valuations couched in varied intonations. Attentive listening to Some Things I Said reveals that we are privileged listeners to a fellow pilgrim. He is one of us. Ferry’s creative genius mesmerizes with the extraordinary way he gives voice to the range of human experiences mentioned in this poem.

His candidness assures us that we are not alone in facing the ineffable complexities of life nor the most haunting question of all:

I cried in my mute heart,

What is my name and nature

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this poem is Ferry’s plaintive appeal to generations yet to come. A superb translator of early and classical poetry, his Epic of Gilgamesh was described by William Moran as “… a work of verbal art.” He excelled at conveying into our present the sense of what the ancient poets said and the sensual impact those poems had on the original audience. Anyone that has done translation work understands how vital it is to put a classical text in its context so as to bring these writings to life. There is an underlying pathos in Some Things I Said as Ferry seeks to provide context for future translators of his legacy of lines that sing.

And how we’re caught, I said,

in language: in being, in feeling, in acting. I said, it’s

exacting.

In this unequalled work of David Ferry’s thought-full artistry, we are greatly favored to be the original audience of the man and his voice.

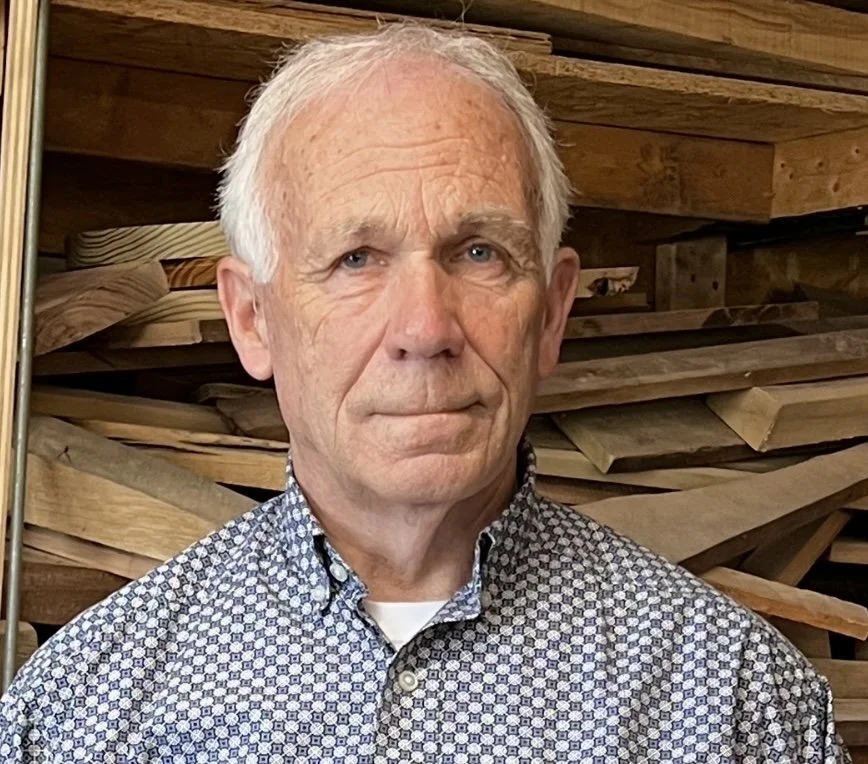

Les Schofield is a writer, artist, and woodworker living in the western foothills of North Carolina. Hailing from a storied southwestern family, he was raised among carpenters, cowboys, and rocket scientists in New Mexico and southern California where he had many adventures before moving among the mountain people of the Appalachians. He is married to Kathryn, a professional folk artist. He is a member of the North Carolina Poetry Society, the North Carolina Writer’s Network, and the National Book Critics Circle. He is currently writing a novel of the American Revolution as it played out in the Carolinas.