“The Heartbeat and the Heartbreak”: Carlene Gadapee’s review of QUERIDA by Nathan Xavier Osorio

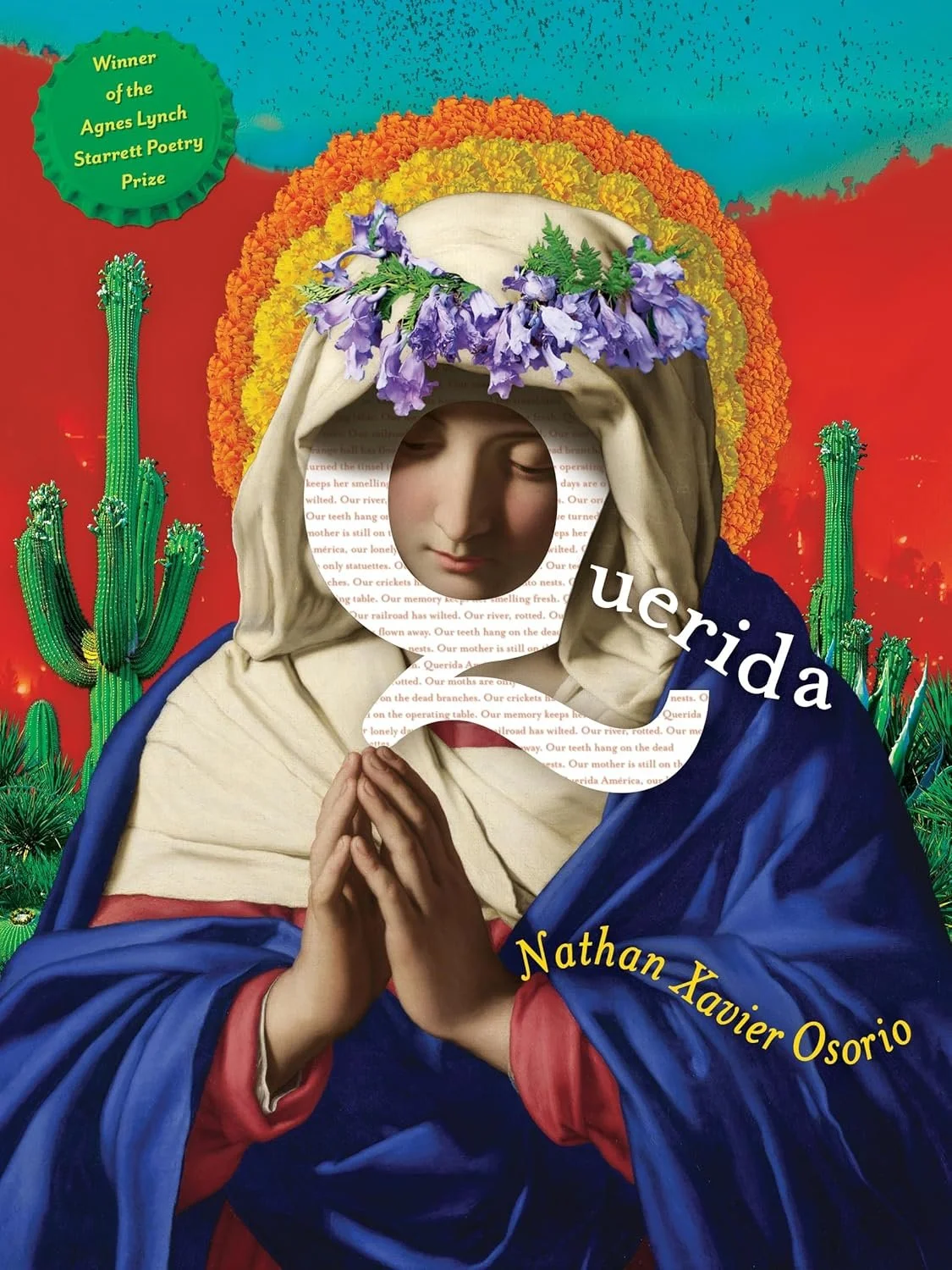

Querida

Nathan Xavier Osorio

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024

101 pp.

Winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize

Baseball. Blue-collar work. Ethnic roots and racism. Joy and sorrow, mixed with music and dust. This is Nathan Xavier Osorio’s Querida, a fine first full collection that really rocks the reader back on their heels. At least, it did me. I had the distinct pleasure of meeting Osorio in Franconia, NH in July when he was just finishing up his residency at The Frost Place as the 2025 Dartmouth Poet in Residence. I attended a reading in the lovely and intimate setting of the Abbie Greenleaf Library, which was filled to the windowsills with people eager to hear Osorio read in person. This collection is both a delight and a challenge; a delight, because Osorio’s imagery and his mastery of both free verse and formal structures flows so easily, and a challenge, because for me, a middle-aged white woman in New Hampshire, the experiences of working-class and poor Americans of Mexican descent are foreign to me. But I am always willing to learn, and Osorio’s ability to weave a tale makes it pleasurable and engaging to follow along his pathways into and around those experiences.

The first poem, “English as a Second Language,” makes it very clear where we will be headed, as we follow Osorio’s speaker, who “nodded submissively to a professor/ who assured me [his] failure was because English was [his] second language.” The language and diction chosen for this poem is richly evocative, and the imagery is both lush and sometimes forbidding, with the speaker telling us that “I too can love/ enough to become a volcano.” The two pages of the poem are literally one sentence, with the poet choosing to use line and stanza breaks to pace the readers’ understanding of the subject matter. The poem comes in waves of thought and image, finally coming to a close as the speaker says,

our roughnecks’

night sweat cooled by the prospect of tomorrow’s new depths

it baited as progress as self-preservation that will not include me

or my pilot or maybe even you, but whoever has and still sits

in the enormous leather chair.

Baseball is a theme that appears several times in Querida. I say theme instead of subject matter because it is not only about the game, but more, what the game represents to the speaker, and, by extension, to the wider group of people who either play or participate in what is often called “America’s Pastime.” The poem “Welcome to the Show,” written in three sections, directs our attention to a slightly different group, those who do the behind-the-scenes, nearly invisible work that makes our leisure possible. We are also asked to consider just who are the players? Where are they from? The speaker returns several times to the question, when (and where) does the game actually begin? Is it in the clubhouse? The parking lot? On the field? Or is it from disparate countries, with many of the players coming from far-away places and

the desperate children hungry/

for more game, for more signs of life cracking from the bats//

of their million-dollar heroes plucked from Cienfuegos,/

Cuba, Culiacán, Mexico, from Incheon, South Korea/

to be American All-Stars.

Or maybe, “The game,/ if not here, must begin someplace further beyond// the office of recent memory.” This is how the first section of the poem ends.

The second section of “Welcome to the Show” is more personal; the speaker ponders adolescence, and he directly addresses the reader throughout. Near the end of this section, the speaker says, “…we must ask—which side of this civilian/ war are we on? Can we ever come back from this moment?” This is one of the almost ontological questions asked in this collection, questions that demand that we spend some time not just with the poems, but with the heartbeat and heartbreak from which they spring.

In the third section of “Welcome to the Show,” we are pulled into a specific memory of a particular night game, which the speaker can “only remember in color” and of “the progression of players whose atoms are electric/ sprinting from base to base till they do their part/ to return home.../ so we can embrace them high and proud,// as if they were our very own.” In this way, the poem raises difficult questions about class divide, racism, and the individual’s part in the dynamic, but it also resolves that there are times and spaces when we are all able to consider ourselves as one group, if only fleetingly.

A heroic crown of sonnets titled “The Last Town Before the Mojave” is interspersed throughout the collection; while this is unusual choice, it serves a real, connecting purpose. While a heroic crown of sonnets is already closely and intentionally linked (after the first poem, the last line becomes the first of the next poem, all throughout until the fifteenth sonnet, which is comprised of the first lines of all of the series of poems), this particular heroic crown, as it is woven throughout the collection, also serves as the thread that binds the work together.

The first sonnet begins with “Hunker down, Heyzuez, if that’s your real name.” The brashness of this line sets the tone for the sonnets that follow; rough treatment, pain, and sorrow are all in these poems, but there is also love, burgeoning pride, and a sense of self that feels like quiet resistance. In the third sonnet, the lines “I am no longer/ surprised when we stumble across the graves” is balanced by the first line of the fourth sonnet, “Wails and the silence of devotion.”

And so it goes throughout; gut-punch lines, heartbreaking beauty, and a group of people within a culture who are just trying to live each day without being shifted to the side, forgotten, or erased.

In the sonnet that begins, “Our impermanence of memory is,” we come to the soul of Querida, as a collection and as a declaration of love by the poet. The sonnet ends with, “So/ if anyone dares to come ask, let them/ know it was us. We drove out the thunder.” This is what the collection does: it stands its ground against faulty expectations, against overt racism and bias, against abject poverty of spirit and flesh, and thus, it “drives out the thunder.” Osorio’s words challenge us, often gently, to examine cultural faultlines and what we are willing to do about them, and what we are able and willing to accept.

The final poem of the heroic crown is devastating; it is both an indictment and a celebration of ethnic dislocation and location. The poem poses a central question when the speaker asks, “Is the crash of inheritance silent?” Ultimately, the readers must search within themselves to consider if there is even an answer.

The poem, “Mami, Tell Me That Story Again” raises another of the central arguments in this collection: what does it take to be seen? What does it mean to be seen? Poverty and hope have a hard time co-existing, but love and gratitude are somehow the result of the shared struggle, of the acknowledgment of inequities that are realities too often both exploited and sanitized. The speaker tells of times when being of undocumented status, imperfect treatment and unnecessary struggles are the result of cultural bias. He says, “Oh, Mami, tell me that story/ again where you tell us we men/ can do better, where you’re grateful/ that medicine came at all to a boy// with no papers….” This poem, like others in Querida, showcases other voices, those of family and elders, that represent a larger culture. The reader will find that, even with the struggle and dismissive treatment, there is little to no anger, just quiet hope, love, and resilience. That is one of the larger lessons that this collection can impart.

The final section of Querida is a series of poems written as rituals. In the poem titled “Ritual for the Implosion,” the speaker’s voice is not masked, but rings true and honest. He starts with, “If you hold it all in, you’ll implode, not violently but slowly like the/ wrought iron vessel sinking into the underwater canyon of a deep well.” Implode, not explode. But the damage is clearly going to happen, and maybe that’s how truth gets told. The focus of the poem is in the second stanza, when the speaker says,

This is where the metaphor ends. Where I refuse to be complicit in any

more acts of violence. I was told to promise, to keep a secret, and instead,

I told my version of the truth. I told them what it feels like to hear your

mother sing for the first time.

Querida, as a full collection, is a loving homage to a culture, despite the challenges and pain that have become generational. What the poems ask of us is compassion, and Nathan Xavier Osorio’s work communicates that request in a way that cannot—should not—be denied.

Poet and teacher Carlene M. Gadapee lives in northern New Hampshire with her husband, several fruit trees, and a beehive. She holds two Masters’ Degrees (MEd and MA-LS). She can be found on Facebook as Carlene M Gadapee, on Instagram at @carlenegadapee, and on BlueSky at @carlenemgadapee. Carlene M. Gadapee’s chapbook, What to Keep (Finishing Line Press, 2025), joins her poems and book reviews in many journals including Allium, Smoky Quartz, Touchstone, Gyroscope Review, Vox Populi, and MicroLit.